what are some of the ways that pollen can travel from one flower to another

Information technology'south 5 a.g. at the UWM Field Station, a natural area about Saukville, Wisconsin, about 45 minutes north of UWM'due south main campus. Biology students, led by postdoctoral researcher Dorothy Christopher, drag some of the hundreds of numbered potted plants from the hoop house and identify each on the outside grass into a slot on a spray-painted grid. Then they don headlamps and trim all the flowers from each plant except for one.

With their controlled environs fix, they are ready for the bumble bees, which come to forage around vi:15 a.m. To accomplish this twenty-four hour period's objective – post-obit the flight of bumble bees that enter their makeshift garden – they have simplified the task past limiting the number of available flowers.

"We utilise the native monkeyflower because their flowers just last a single morning," says Christopher, who works in the lab of Jeffrey Karron, professor of biological sciences in the Higher of Messages & Science. "When we come up in, the just-opened flowers have a full pollen load."

A hefty pollen load is what the bumblebees are looking for, and they tend to stick with a particular plant species that delivers. As they forage, their bodies are covered in pollen, with the top layer picked up from the flower they are currently visiting and the deeper layers from flowers on previously visited plants.

Karron is at the forefront of quantifying paternity patterns among flowering plants. Ultimately, he'southward interested in what influences successful establish reproduction, and why nearly all flowering plants are hermaphrodites, meaning that male and female parts are present on each flower.

Karron's piece of work is important, says Randall Mitchell, a University of Akron professor of biological science who'due south a leading scientist in the field. Understanding the complexity of pollinator-enabled reproduction is necessary to protect crops, wild plants and the viability of endangered plants.

For plants to make seeds that turn into potent and healthy new plants, much of the reproductive procedure rides on the pollinator'south choices. Although a constitute'southward flowers contain both the eggs and sperm, pollen begins the procedure of linking the two within a bloom to produce the offspring – seeds.

At the UWM Field Station, Jeffrey Karron's research is discovering more about the relationship between bees and the flowers they visit.

By combining genetic information with meticulous pollinator-mapping, Karron (pictured) has answered questions about institute reproduction that no one else has been able to. (UWM Photograph/Troye Fox)

When a bee visits a flower, its body gets covered in pollen, which then mingles with the pollen it's already picked upward from other flowers.

Researchers attach pipe cleaners to monkeyflower plant stalks to collect and rail data. The color of the pipe cleaner denotes the date a bee visited the establish. (UWM Photo/Troye Fob)

At the UWM Field Station, Karron's research group has made a number of discoveries about the reproductive strategies of plants. (UWM Photo/Troye Fox)

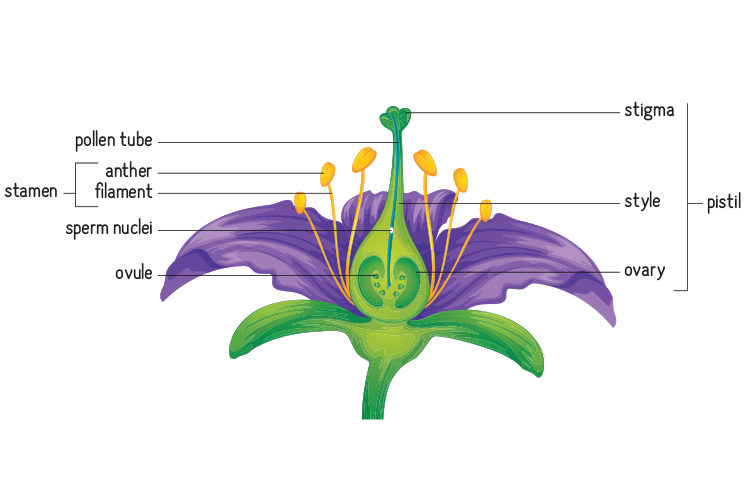

But pollen first must be moved from a male part of a flower, called the anther, to a female person part, called the stigma. And pollen tin can come up from the same plant or from flowers on other plants of the same species. In fact, pollen from multiple monkeyflower plants could be left during a unmarried bee's visit.

Complicating matters farther, institute reproduction tin can happen in two different ways. A bloom'due south female person parts can receive pollen from their own anthers or from those on different plants of the aforementioned species – any institute the bee last visited.

When pollen comes from flowers on the same plant, information technology'due south called self-pollination or "selfing," while reproduction involving flowers from two different plants is termed cantankerous-pollination. Seed production after selfing is considerably lower than cross-pollination, and the resulting seedlings are non as healthy. The lowered fitness is similar to the consequences of inbreeding in animals and results from mating with a express gene pool. Cross-pollinated seeds grow into a much healthier second-generation found.

The source of the fertilizing pollen is considered the male flower that sired the seeds, while the flower where the pollen was deposited is the mother. Because of these unlike possible outcomes, pollinator behavior matters, and information technology's important to know which flowers a bee visited, and in which society.

"When a bee visits the start flower on a institute, 80 percent of the resulting seeds are cantankerous-pollinated," Karron says. "By the fourth dimension it alights on the fourth flower of that plant, most all the seeds are cocky-pollinated."

Of import as information technology is to establish where the pollen for each seed came from, that information doesn't come easily, given nature's onslaught of variables. But through cleverly engineered experiments, such as Christopher'due south single-flower bee garden, Karron tracks the bees. He tin can decide where they get together their pollen, and where they leave it, and he establishes the monkeyflower'south mating histories.

Inside his hoop house at the Field Station, an experiment's monkeyflower plants are numbered and, by the terminate of each study, pipage cleaners of various colors are attached to some stalks. Similar a hospital patient'southward medical bracelet, the pipe cleaners are part of a detailed record-keeping system. They denote where a flower had been in the garden, and the pipage cleaner's color indicates the date of a bee visit.

Karron doesn't rely on homo ascertainment alone. Each plant used in an experiment is genotyped earlier it's moved outside and bee mapping begins. This fashion, the researchers have a "signature" that they tin can later match to a seed's genetic profile.

"We put in a ton of piece of work on the front end finish," Christopher says, "and so that we can differentiate pollen from the various plants. That's how we can track how far the pollen has traveled."

UWM'south Field Station provides the swath of undisturbed nature required for the research, which accounts for not but ecological factors, similar pollinator affluence, merely also genetic variables, similar the shape of flowers. "I can replicate populations at the Field Station in order to look at how their mating habits modify nether different conditions or environments," Karron says. "And I tin easily clone institute populations past simply dividing the plants. You can't practise that with birds or mammals."

As labor-intensive every bit these experiments are, the most challenging part, Karron says, is managing the scale. At the end of his most recent study, eight,000 seeds were harvested and genetically analyzed.

By combining genetic information with meticulous pollinator-mapping, Karron has answered questions nearly institute reproduction that no one else has been able to. Mitchell, a longtime research collaborator, says Karron is identifying what influences bee behavior and connecting it to their evolutionary impact on plant reproduction. It'south allowed Karron to start unraveling why the hermaphrodite reproductive strategy is so successful, despite self-pollination existence a handicap to long-term plant survival.

The advantage, Karron has shown, is that dual sex roles double the number of potential mates a parental plant could accept. That increases the genetic diverseness of seeds, diverseness that ensures the overall hardiness of seedlings.

Karron's inquiry group has made other long-sought-after discoveries. They demonstrated that mate combinations for individual flowers on the same plant can differ dramatically. That is, the pollen that produced seeds in any two flowers could have been from the constitute itself or from a bloom of the same species miles abroad.

They were the first to demonstrate that pollinator responses to showy floral displays increment the selfing rate for plants. The reason? After visiting 1 bloom, bees volition oftentimes "play a trick on or care for" to the next closest flower, oftentimes on the aforementioned plant.

And Karron's research team showed that the presence of a competing angiosperm species boosts selfing patterns in monkeyflower because the competitor often sidetracks the bees. Cross-pollination simply occurs when the bees alight on different monkeyflower plants consecutively. Even the species of bumblebee (there are 5 at the UWM Field Station) tin can change the mating patterns, he says.

Tracking wild pollinators and correlating their pollen quantitatively with seed paternity is painstaking piece of work that few plant biologists take attempted. But Karron'south fastidious field work has yielded plenty of scientific evidence that proves a found's reproductive strategy is anything but random.

"I love to design evolutionary experiments," he says. "If nosotros do information technology right, we tin can go the bees themselves to explicate their behavior."

Source: https://uwm.edu/news/where-the-bees-are/

0 Response to "what are some of the ways that pollen can travel from one flower to another"

Post a Comment